Reasonable Credulity

One of the most applicable cases of the school of critical thinking is Ritola’s argument that it takes a certain degree of critical thinking to discern what is actual expert opinion. This is as important as ever today with our current political climate. Nearly every person who is introduced on Fox News or MSNBC is an “expert this” or “expert that”, but very rarely do we as a society go online to fact check their credentials. In addition, Ritola’s thesis expands beyond expert opinion to opinion in general. As a society, it is important not just to be able to identify who is an expert and who is not, but what is fact/news and what is opinion. While “Fake News” is certainly an issue, we might argue that strongly disguised, opinionated news is not only more rampant, but even a bigger problem than actual fake news. There is no longer objective news, merely opinionated versions of news/events that come from biased media. Interestingly enough, in the age of technology and social media, Ritola’s thesis may place a bigger importance on identifying reliable sources. In other words, it now takes a degree of critical thinking to know which websites and forums on Facebook and other sites are actually credible. America will always be divided because there is such a distinct sentiment from liberals and conservatives, but if everyone were presented the same news, in a non-biased way, and if we had better critical thinking skills to identify biases, our society would be much more cohesive and understanding of one another.

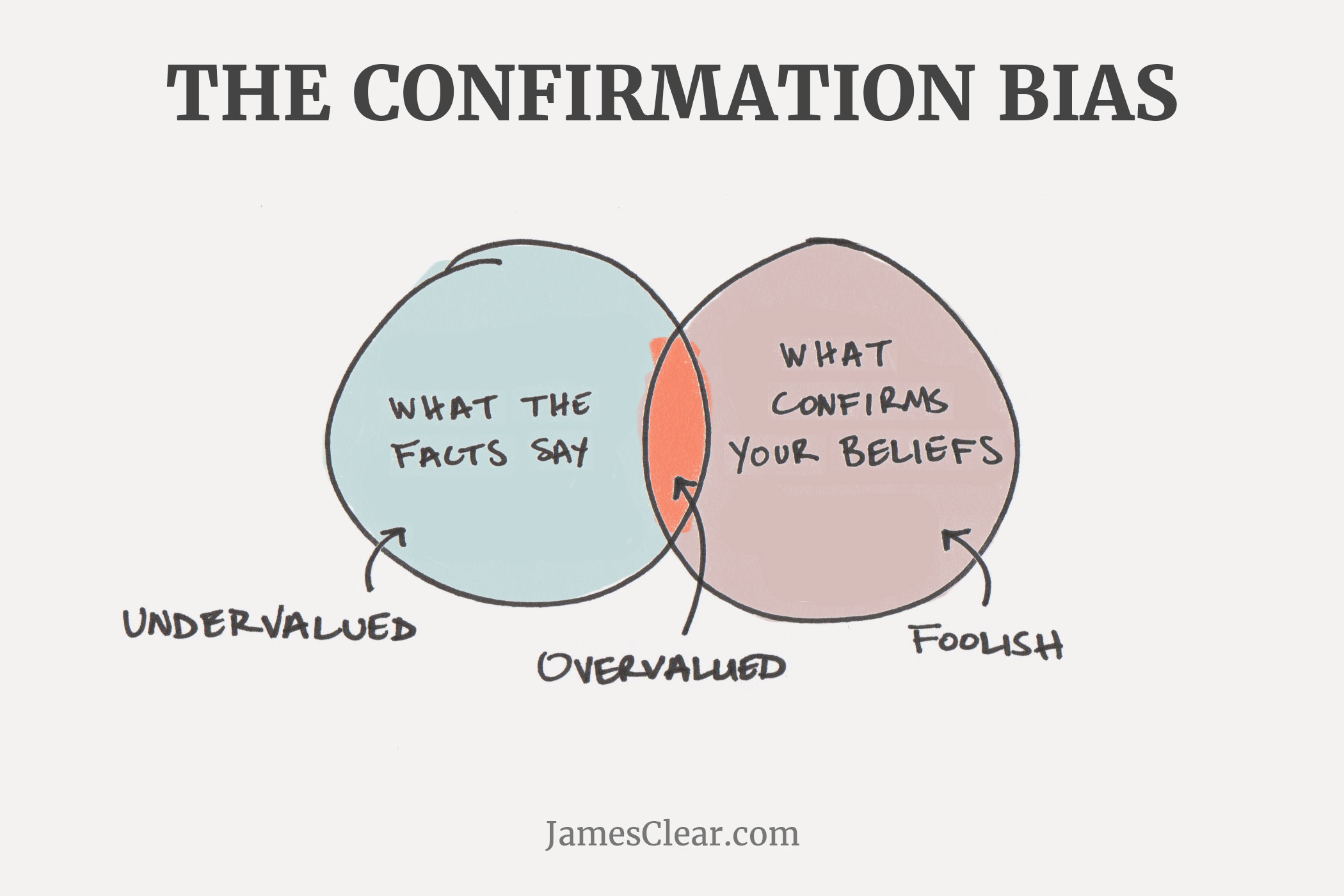

Confirmation Bias

As Caleb W. Lack argued, there are a number of reasons why our brains cannot be trusted. For instance, human beings carry several forms of cognitive biases, which are consistent patterns of discrepancies in judgement that can result in incorrect conclusions and beliefs. This condition makes us perceive the world in a distorted way, so it is important that we are aware of these biases to try to avoid them.

Among the most common biases, one particularly salient type is “confirmation bias.” Confirmation bias is the tendency that human beings have to only pay attention to information that further confirms their preexisting points of view. People choose to remain in their comfort zones by only listening to arguments they already agree with.

One example was a high school class about feminism. Not surprisingly, most of the students in the class were feminist girls who were already very aware of what feminism was and completely agreed with its arguments. Students who were more conservative or even sexist would steer clear from that class, because they did not want to be exposed to ideas that they did not agree with.

One problem here is that if people don’t let themselves be exposed to different ideas, then people will never change their minds. The world today is becoming increasingly more ideologically polarized and intolerance is reaching new heights because people refuse to listen to and acknowledge new or different arguments.

To further the problem, the way most search engines and social media algorithms are shaped is that they target users with what they think their profile is; we are therefore more prone to receive information about things we like and agree with, and are not exposed to other points of view.

Egocentrism

According to Richard Paul, egocentrism is the most significant barrier to development of critical thinking (Paul, 331). The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines egocentrism as an excessive interest in oneself and concern for one’s own welfare or advantage at the expense of or in disregard of others. Paul regards egocentrism as a function of our irrational mind. He argues that our irrational mind becomes the default mechanism when our rational mind is underdeveloped. The exercise on pg. 335 discusses how our egocentric tendencies affect our decision making. The exercise is a breakdown of our rationality on a specific event in which we put our interests before someone else’s. The exercise has a resounding influence on the development of our critical thinking skills, and we hope it will carry forward to our career. We slowly started to integrate empathy and radical open-mindedness in our thought processes as we listen to others’ point of views. In listening to the opposing point of view, we try to understand what position they are trying to take, how they come to hold such a position, and what they are trying to get out of the conversation. By taking the time to assess the other side, we find that we are in a much more informed position for response without immediately feeling the urge to argue our side alone. On the other hand, we have also started to think about our own response to the specific topic. Before responding, we have to think about what position we will hold, why we are holding this position, and what we are trying to get out of holding this position. As a result, we are much more cognizant of what we say and how we say it. We realized that we have started to control ourselves in situations that incite strong emotions, especially when the other side has severely conflicting views. Paul’s breakdown of the opposing side and our own logic will surely aid in complex and critical situations. The exercise will help develop our emotional intelligence which is a strong trait to have as a leader and, most importantly to Paul, as a critical thinker.

Fixed versus growth mindset

There are two basic approaches to capacity for change: a fixed mindset and a growth mindset. A fixed mindset holds that we are born with a certain level of aptitude in various skills, of intelligence, and even of willpower which we cannot change. Because people with a fixed mindset do not believe in the possibility of self-improvement, they focus instead on demonstrating the skills and qualities they currently possess to themselves and to others. A fixed mindset engenders avoidance of challenges, in case failure might reveal that a capability threshold is lower than the mind previously believed. Thus, although a fixed mindset may result in fewer failures in the short term, in the long run it inhibits development and growth. It is easy to see how simple beliefs we repeat to ourselves and others — such as, “I am a procrastinator,” or, “I am not a STEM person” — enable the avoidance of putting effort into positive change; these statements imply that you have always been, and always will be, a certain way.

A growth mindset, on the other hand, embraces and even hungers for mental and emotional challenges. A growth mindset believes in its ability to improve through hard work and experience. A growth mindset is more likely to view failure and criticism as learning opportunities, and is less likely to shy away from challenges and judgement. As such, it is more likely to produce thoughts along the lines of: “I have not done will in STEM classes thus far. However, I think that I could become better at science and math if I put in the effort. I will try to improve by enrolling in a physics class next semester.” The growth mindset is concerned with stretching its abilities, and is therefore more likely than a fixed mindset to maximize its potential.

When considering the growth mindset, it is important to remember two things: First, we must keep our expectations realistic. A growth mindset does not mean you can accomplish anything and everything; it only means that you can improve. For example, not everyone can become an NBA player by working hard at it. However, everyone can get better at basketball, as compared to their current skill level– and perhaps win their university’s intramural league. Second, although it is often talked about and researched in an educational context, the growth mindset is not specific to intelligence. You can apply the growth mindset to everything from practical skills, to interpersonal skills, to moral progress. Also, if you assume that other people have the potential for growth in these areas, you will probably have a different approach to interaction with them and to changing others’ minds.

For more, watch this video on “the most powerful mindset for success”:

Group members: Nash Hale, Sabrina Magalhaes, Kenneth Reyes, Jessica Wahl

Sources

Popova, Maria. “Fixed vs. Growth: The Two Basic Mindsets That Shape Our Lives.” Brain Pickings, 18 Sept. 2015.

“Decades of Scientific Research That Started a Growth Mindset Revolution.” Mindset Works, 2017.

“Egocentrism.” Merriam-Webster, Merriam-Webster, www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/.

Clear, James. “Fixed Mindset vs Growth Mindset: How Your Beliefs Change Your Behavior.” James Clear, 30 July 2018.

Paul, Richard, and Linda Elder. Critical Thinking: Tools for Taking Charge of Your Professional and Personal Life. 2nd ed., Pearson Education, 2014.

Lack, Caleb. “Why Can’t We Trust Our Brains?” Springer Publishing Company, 2016

Ritola, Juho. “Critical Thinking Is Epistemically Responsible.” Metaphilosophy, vol. 43, no. 5, 2012, pp. 659–678.